Table of Contents

- Inputs and Outputs of Gardens

- Why Are Garden Inputs Important?

- Are Inputs Required for Gardens?

- Which Inputs to a Garden Occur Naturally?

- Reducing Garden Inputs

* Our articles never contain AI-generated slop *

Reducing garden inputs not only means reducing expenses, it also means fewer trips to the store. Less fuel burned transporting inputs across continents. Reducing the miles your nutrients travel by keeping more of them on your land for longer. Cycling nutrients more times before they leave your garden or farm. Patching up all the nutrient outflows of your system so you can hang onto more of what you've got.

These days, reducing my inputs for the garden is of paramount importance because this directly reduces expenses. This is actually done indirectly, through reducing garden outputs to balance out a reduction in inputs.

Inputs and Outputs of Gardens

Like any complex system, a garden has both inputs and outputs.

Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links. Refer to the privacy policy for more information.

These largely fall into 3 categories:

- Water

- Seeds

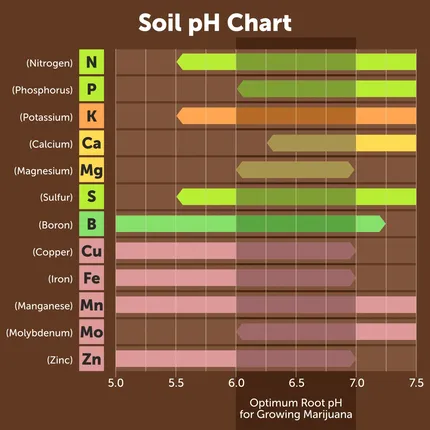

- Nutrients

While water and seed-saving are both equally-important topics, we've covered them both elsewhere:

Here, we're mainly focused on the inflow and outflow of nutrients from out garden system. When we discuss garden inputs and outputs in this article, nutrients are what we're focusing on.

What Are Garden Inputs?

Thinking back to the first time I ever started an outdoor garden, I'm absolutely mortified at the price that I paid for all the soil, compost, mulch, amendments, organic fertilizers, kelp meal, alfalfa meal, rock, dust, etc.

Many hundreds of dollars later I had a garden that grew some pretty dang good vegetables, but at what cost!??

Garden inputs are these bags of soil and nutrients which you purchase as additions to your garden.

Join The Grower's Community

A free & open space for anyone who is passionate about cultivation 🌱

Check It Out!

They come from the outside world, away from your land, are generally shipped in, you bring them to your land, and you pay money for them.

What Are Garden Outputs?

Garden outputs are the outflows of nutrients from your garden.

While it's easy to visualize all the bags, products, and truckloads of additions you haul in for your garden, it's more difficult to wrap your head around all the nutrient outflows

Why Are Garden Inputs Important?

Garden inputs are the inflows of nutrients which will replace the garden outputs.

If your garden outputs exceed your inputs, you will deplete your soil and reduce your yields and overall garden health over time.

If your garden inputs exceed your outputs, you will improve soil health, nutrients, organic matter content, plant health, and yields over time.

Are Inputs Required for Gardens?

Not necessarily! It is possible to garden indefinitely on a piece of land without ever hauling any nutrients or amendments onto the land.

While that's a great goal to strive for, it's not likely to happen in your first few years - especially if you're new to regenerative agriculture.

Instead, I suggest the goal of gradually reducing your inputs as you learn how to create a more self-sustainable system, learn to sequester more carbon and nitrogen, and to reduce outflows.

A series of small improvements to mindset and technique will allow you to transition from a heavy reliance on inputs to low or no reliance on inputs eventually. Be patient during this transition and learn all that you can about soil-building!

Which Inputs to a Garden Occur Naturally?

Some garden inputs happen without human intervention, bringing some of the constituents required for soil and plants without effort or expense to the gardener. These include:

- Sunlight

- Rain

- Carbon (sequestered by all plants)

- Nitrogen (sequestered by nitrogen-fixing plant species such as legumes)

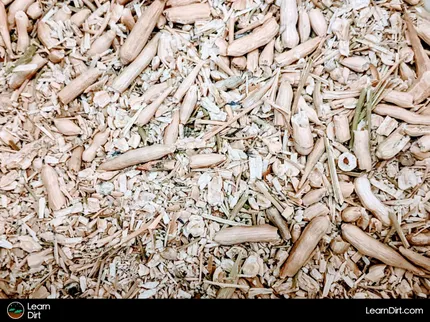

Reducing Garden Inputs

Today, when I start a new garden, the first thing I do (along with irrigation) is start a compost pile.

I divert my food scraps, coffee grounds, tea leaves, shredded cardboard boxes, and junk mail (non-laminated) straight into my compost.

This immediately begins building incredible nutrient-rich soil from day one!

Some of the compost I build will be used as an amendment when starting new bed. Most of it, however, will go towards seed starting mix that I'll utilize for germinating seed indoors.

It's difficult to make enough compost to power an entire garden. I'd recommend you try, though you may not be able to produce enough nutrients for the whole garden. That is, unless you have leaves, branches, and trimmings from a large property or acreage.

In a small apartment, you may find it difficult to produce enough compost to power, your community garden plots, for example.

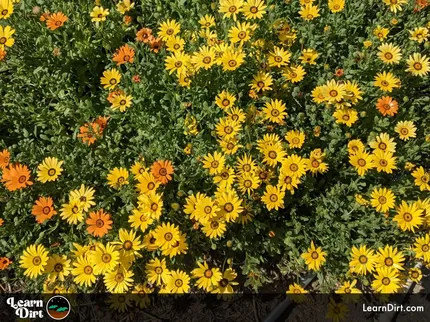

Input Reduction via Cover Crops

When compost is not enough, it's time to utilize the ultimate soil-builder: cover crops!

The next thing I do is lay down drip lines, a little compost, and plant a cover crop such as a heavy grass to build a lot of carbon in a very short period of time.

I will chop and drop this in place for a full season.

Dig Cool Merch?

Next season, I will intersperse nitrogen-fixing crops in with the grass to help temper the carbon and add much-needed nitrogen.

I will chop and drop both of these in place all season.

Third season will be heavier on the nitrogen-fixers and I'll reduce the amount of grass.

At some point, depending on the quality of the starting native soil, this cycle can be repeated as necessary until you can grow your first real crop. I'll intersperse nitrogen fixers with my crops, which will be chopped and dropped all season to feed the microbiome. New soil is constantly being built.

If the native soil is heavily compacted like much of ours, in Tucson, I may plant a cover crop, such as daikon in the winter, or sweet potatoes in the summer as a way to break up those compacted soil's, and caliche naturally.

I can also plant crops for deep roots like alfalfa, which will help break through some of the tougher layers of dirt. These methods are far easier and more effective than telling my hand, which I rarely would ever recommend.

In the first few years, I'll continue to intersperse cover crops in with my vegetables, or I'll grow full cycles of cover crops in between cash crops cycles.

If I grow nothing but cover crops in a bed, I will rotate to a new bed for cover cups next cycle. This cover crop rotation works well on larger tracts of land with more plots, whereas I find interspersing cover crops in with vegetables works great on very small scales, especially in highly diverse polyculture plots.

That's all for now, thanks for reading!

If you have any questions, comments, or would like to connect with fellow gardeners, head on over to the forum and post there.

![Black Dirt Live Again [Green]](/media/product_images/black-dirt-live-again-[green]_shirt_260x260.png)

![Black Dirt Live Again [Purple] Sticker](/media/product_images/black-dirt-live-again-[purple]_sticker_260x260.png)