Table of Contents

- Understanding Soil Health

- Improving Soil Quality Through Regenerative Practices

- How Long Does It Take to Improve Soil?

- Consequences of Ignoring Soil Health

- Soil Remediation Examples

* Our articles never contain AI-generated slop *

Soil improvement and remediation is so important for every organic gardener or farmer to understand, and is one of the pillars of regenerative agriculture.

Here we'll discuss how to improve soil quality, and consider the time scale in which you're going to do it.

First, let's talk about soil health in general - how to assess your soil quality and understand its needs.

Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links. Refer to the privacy policy for more information.

Understanding Soil Health

Without knowing anything about your soil, it's going to be very difficult to understand what needs to be done to improve it.

Gaining insight into your soil health is the first step towards a path forward.

Let's discuss some ways you can understand what you're working with before prescribing solutions.

Soil Testing

Before any soil remediation efforts, it's crucial that you understand the profile of your soil. Knowing what nutrients your soil has in abundance and what it's lacking will inform your remediation plan and show you where your focus needs to be.

There are thousands of organic amendments, nutrients, and supplements which can be added to your soil. Until you perform a soil test, however, you'll just be guessing at anything you add.

This is a recipe for wasted money, time and effort. Worse still, you may inadvertently cause nutrient toxicities that can harm your plants if you're guessing at what to amend.

Join The Grower's Community

Your space to connect, learn, and belong 🌱

Check It Out!

This is why soil testing is so important, so you aren't taking shots in the dark.

If you're ready to jump into analyzing your soil, I suggest focusing on the following critical aspects to assess what you're working with:

Soil Biology

Soil biology is more complex and difficult to understand than soil nutrients or texture.

Unless you have a microscope and have taken classes from Dr. Elaine Ingham's Soil Food Web School, you'll have trouble understanding the extensive microbiome and its food chain and health.

That said, you can assess your soil's biological health in simple ways to gain a cursory understanding of whether your dirt is alive or dead.

If you can't identify life forms when digging in your soil, it's likely very dead and needs a lot of work.

If, on the other hand, your soil is crawling with woodlice, mites, worms, grubs, beetles, ants, springtails, etc. then your soil is alive and biologically active.

Additionally, the presence of mycelium and fungal hyphae are great signs of biological health, as is the presence of mushrooms.

As a general rule of thumb: the more life you can identify in your soil, the healthier it will be. Living soil is the goal of regenerative gardening and of organic growing in general.

Soil Nutrition

There are 19 macro- and micronutrients required for plants to thrive, and all 19 must be present in your soil in order to provide proper nutrition to your plants.

Check out this article for a full list of soil nutrients and the common organic amendments which provide them.

As mentioned above, a soil nutrition test is the best way to assess which nutrients are available in your soil and in what amounts.

This will inform you as to what nutrients you'll need to amend, and in what amounts. After you get your soil nutrition analysis results, refer back to the amendment chart to understand what you can add to correct deficiencies.

Improving Soil Quality Through Regenerative Practices

Regenerative agriculture seeks to regenerate soils and improve soil quality over time, organically. If you want to improve your soil quality over time, regenerative agriculture is the way to do it.

Let's talk about some of the basic tenets of the regenerative paradigm which will help you to remediate your dirt.

No-Till

Heavy tillage was once considered essential for agriculture, and has been practiced for most of the agrarian age. Many gardeners and farmers still practice plowing and tilling their fields today.

Thankfully now we know better.

Recent advancements in microscopy and soil science have given us tremendous insight into soil and microbiome health.

Through study of soil microbes and their lifecycles we've come to recognize the importance of a thriving microbiome for the health of plants and of the ecosystem.

We know now that heavy tillage wreaks havoc on delicate mycelial networks and beneficial soil bacteria, archea, flagellates, nematodes, etc.

Dig Cool Merch?

We understand that plowing releases enormous amounts of carbon and nitrogen from the soil, which volatilize back into the environment - the very nutrients we work so hard to sequester in the first place.

We recognize that exposing worms, woodlice, grubs, and larvae in the soil to birds and predation through heavy tillage is extremely foolish.

We see that the healthiest soils on Earth are found in forests - ecosystems where soil is never tilled.

No-till gardening seeks to replicate nature's most-productive ecosystems and recognizes that nature never tills her soil, yet plants absolutely thrive.

If you'd like to learn more about no-till gardening, check out this article to keep reading.

Chop & Drop

Building on the no-till ideas above, chop and drop also imitates forest ecosystems by allowing plant trimmings, leaves, branches, and plant stalks to fall to the ground.

Plant trimmings and the previous cycle of spent plant matter are utilized as a mulch for the next season. This serves three purposes:

-Chop & drop acts as mulch, to cover and protect your soil and delicate microbiome, lock in moisture, and keep the hot sun off your dirt.

-Nutrients from spent plant matter are returned directly back into the soil, without the 6+ month time delay of running them through a compost pile first.

-Decaying leaves, sticks, branches, and stalks provide far more food for your soil decomposers to consume than finished compost does. By providing fresh chop & drop each season you give your detritivores something to chew on that will keep them happy.

If you'd like to learn more about chop & drop, check out this article here.

Cover Crops

The true holy grail of soil-building, cover crops are pretty much the best thing you can grow to improve your soil quality.

After water, carbon & nitrogen are the two most-important nutrients for both soil and for plants.

Cover Crops for Carbon

All plants are capable of taking in carbon dioxide from the air and converting it into carbon-based sugars. While much of this carbon is exuded from the plant roots and fed to your soil microbiome directly, some carbon remains in the body and structure of the plant.

This means you can compost any plant, whether in a pile or in situ as chop & drop in order to add that carbon to your soil.

A forest grows on a fallen forest, as they say. The carbon from a previous generation of plants is the most crucial element for creating soil. Utilize it.

Cereal grasses are often grown for this purpose as they're one of the fastest-growing plants and can be chopped & dropped not long after planting. They continue to produce more carbonaceous plant matter after numerous cuttings and make a fantastic mulch. Cereal grains and grasses such as rye or oats in the cool season, and millet or sorghum in the hot season make great choices for quick carbon input into your system.

Growing some plants only for adding carbon to your soils (rather than for consumption or sale) is a great way to give back more to your dirt than you take.

Over time, the net positive carbon inflow from growing cover crops and grasses to feed to your soil or compost will yield higher and higher quality soil, a healthier ecosystem, and improved yields and crop health.

Cover Crops for Nitrogen

Likewise, a subset of plants known as nitrogen-fixing plants are capable of taking in nitrogen from the air (through a symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing bacteria) and converting it into solid-form nitrogen.

Some commonly grown examples of nitrogen-fixing covers include clover or alfalfa during the warm season, and vetch or winter pea during the cool season.

By chopping & dropping (or composting) these nitrogen-fixing crops, you're able to add nitrogen to your soil.

Many cover crops are chosen specifically for their ability to fix nitrogen. This means many cover crops pull carbon and nitrogen from the air and sequester it. When added back to your soil, the residue from these plants yields a net-positive input of both these primary macronutrients.

Cover Crops for Scavenging Nutrients

Additionally, some cover crops are grown for their ability to scavenge nutrients - that is to pull up nutrients which have washed down deep into the subsoil and become inaccessible by shallow-rooted plants.

Scavenging cover crops have very deep root systems and can access deep nutrients and bring them back to the surface.

Some covers commonly used for scavenging nutrients include alfalfa, clover, chicory, and trefoil.

Chopping & dropping or composting these scavenging cover crops then provides the nutrients to your topsoil which they've pulled up from down deep.

Cover Crops for Tillage

Some cover crops are grown for tillage, in order to break up compacted soils.

These are generally root veggies such as daikon or tillage radish, sweet potatoes, and other crops with deep taproots or abundant tubers.

Rather than damaging mechanical tillage or manual broadforking, tillage crops and deep-rooted plants can make your life easier by breaking up soil with minimum disturbance.

If you're short on time and would rather work for it, though, these great broad forks are made in the USA by a small biz and make quick work of aerating and breaking up your dirt.

Left in the soil to decompose, these root crops provide housing for bacteria and fungi as they break down and are a slow-release form of nutrients right where new plant roots need them.

Taproots left in soil also provide channels for water to run down, and better-infiltrate down to the subsoil

There are many other uses for cover crops and we've just barely scratched the surface here. To dig deeper into cover crops, check out this article.

How Long Does It Take to Improve Soil?

Healthy plants are just a side-effect of healthy soil. Once you get your soil right, the plants nearly grow themselves!

If you're determined to grow some great organic produce, then by now you should already be dedicated to the goal of improving your soil quality.

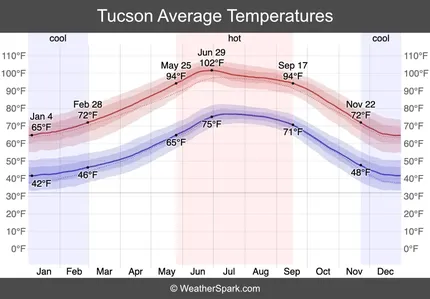

Remember, this is a long-term project that will take multiple years. This is doubly-true in climates and regions with severely depleted or desertified soils.

Unless you've got enough money to fill your space 100% with the highest quality soil on the market, you're going to have to exercise patience along the path to great soil.

As a general rule of thumb, the less money you want to spend the more time it will take. This is heavily affected by space, as affording enough potting soil for 1 small plant is not on the same scale as affording enough soil to power whole fields. The larger your planting area, the more likely you'll want to take a long-term approach to building soil yourself with minimal inputs.

Consider also the quality of your starting soil. Improving coastal soils is a much easier task than improving desert soils. Forest soils may need no improvement at all. Environments with lower-quality starting soil will demand more effort and time from you for the remediation process.

Consequences of Ignoring Soil Health

Too many gardeners make the mistake of ignoring soil health. Focusing more on plants than on the microbiome and soil nutrients. Overlooking the microscopic world in favor of the macroscopic.

Often this neglect happens as a result of a lack of knowledge, combined with the 'conventional' agriculture mindset of extracting the maximum benefit from it this season.

This short-sightedness comes at the cost of long-term soil health, and leads to soil depletion and erosion over time.

Slowly, the organic matter levels drop, trace elements become scarce, macronutrients are depleted, water retention rate plummets, and decreasing soil infiltration rate ensures the soil becomes a lifeless, drained, extracted testament to human ignorance.

That's how you start a dustbowl, don't be that person!

Short-sightedness never got anyone anywhere. Don't sacrifice your soil health 5 or 10 years from now, for maximum benefit this year. You'll regret this down the road if you aren't building anything lasting in your soil.

Instead, learn about the methods mentioned above for improving your soil quality over time, and work these into your long-term plan for your garden, farm, beds, orchard, or planters.

These methods can work at any scale - even a window sill planter can benefit from a proper crop rotation and a couple cover crops.

Cover crops are my favorite method of building soil. Simply put, they are incredible. Once you start growing cover crops you'll never go back!

Soil Remediation Examples

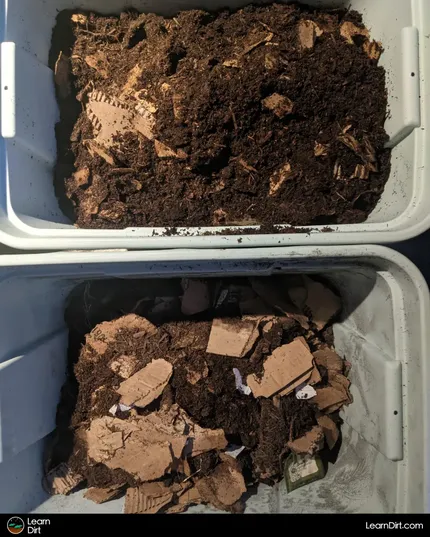

Here a peach tree was standing in sand with a pH of 9.0+ and almost no organic matter content in its soil. Heavy compaction was a substantial issue as well.

The first step towards soil remediation was to apply a heavy wood chip mulch to cover and protect the soil. The wood chips were inoculated with mycorrhizal fungi, as well as beneficial bacteria and red wiggler worms.

Over time the wood chips began breaking down and adding more carbonaceous organic matter to the deprived soil. this helped aid in moisture retention and improved the water infiltration rate so that the peach tree could capture and retain more precious water during rain events.

I was able to establish hairy vetch, clover, and winter pea in the winter to help build nitrogen.

With the monsoon rains I planted millet, sudangrass, and pumpkin to rapidly build carbon.

Alfalfa, buckwheat, and cowpea also went in during monsoon for nitrogen fixation.

All cover crops were chopped + dropped in place. Trimmed limbs and suckers were also chopped + dropped into the tree basin.

Soil quality gradually began to improve, and 18 months into the remediation effort the tree put out the first large flush of fruit that it had in years.

I'm hopeful for the future of this peach tree as the soil continues to improve. It will take time for the nitrogen and organic matter to continue to work their way down to the root zone, so patience is key.

I've observed woodlice, grubs, ants, and fungal hyphae in the soil where I could find no trace of life before the soil improvement project began. All are great signs!

The worms I introduced also began to thrive and their population multiplied with the abundance of decomposing organic matter for them to eat.

That's all for now, thanks for reading!

If you have any questions, comments, or would like to connect with fellow gardeners, head on over to the forum and post there.